by John Wolcott

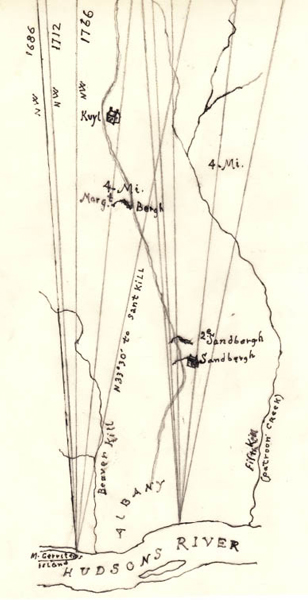

The next piece in the puzzle of “Where is Trader’s Hill?” is an amazing very old parchment map in the Albany City Engineer’s collection. It is the only map known to show Margriets Bergh, and was drawn in January 1773 by Jeremiah Van Rensselaer from a survey done by himself in 1772. This survey and map were ordered by the City in an effort to correct a series of mistakes in a former survey of it’s bounds. The City Charter of 1686 had specified the boundaries of Albany to be a 16 mile long parallelogram. The two sides to run “due north west” from fixed points on the bank of the Hudson, one at the north side of the City, the other at the south of the City. It turned out that “due” was not a good choice of a word. Governor Dongan worked hard as governor but he wasn’t a surveyor. After a few years when at the first survey of the City bounds, the city fathers (that’s all that we entitled to then) interpreted “due northwest“ as by the compass. The trouble with this was that the City Surveyors prior to Van Rensselaer never knew about the annual variation of the compass and shiftings of earth’s magnetic poles. Prof. Henry Gellibrand’s exposition on magnetic variation was published in London 1635, and it’s information, did no reach Albany for a long time. 137 years? Yes! I guess that’s a little of cultural/scientific lag, and the Charter specs appear still not understood by local officialdom in 1773. However, they may have been understood by the surveyor. The former City survey lines displayed all across Van Rensselaer’s amazing map with helpful reference features, are unintentionally a guide to locating many sites in the Pine Bush including Margriets Bergh. The City Fathers were informed that all of the successively mapped north west lines had been shifted over time by magnetic variation and that “natural” (geographic) northwest “remains constant.” Their response was something like, “We’ll stop this shifty looking magnetic motion un-natural nonsense.“ They then went on to declare the City bounds to be forever fixed and securely anchored down along “natural northwest.” This lasted only until 1800, when replaced by another notion. All mistakes, but they are helping us now, none the less. So important was this “fixing the shifting,” at the time, that mile distances were ticked off along the map’s natural NW boundary version. It turns out that the edge of Margriets Bergh is sketched on the map along the south natural NW city line, a little east of the four mile tick. Remember to not always depend on officialdom, value variation in nature, in people, and in your compass readings, and always seek the high ground.

Getting Closer

The “Natural” NW version of Albany’s south boundary line can be fairly easily re-created on a modern topographic map. If you want to try itself yourself, use preferably the 7&1/2 minute Albany Quadrangle of 1953 updated to 1980. Draw a north south line starting at the outer bend of Gansevoort Street in the South End. (This was where Albany’s south boundary line was to start by directions in the Dongan Charter). This north south line has be parallel to a meridian line indicated at the top and bottom edges of the map. This will align with true north. Now take a round protractor, or cut out a paper one by the directions on page 36 of Bjorn Kjellstrom’s Orienteering Handbook. Pages 109-114 describe “variation“ and the magnetic north pole. Now draw a line at 45 degrees west from your vertical meridional line. This is 315 degrees on a round protractor and makes for precisely Geographic, true, or “Natural” North West here. Now measure off four miles by the topo map’s scale along this NW line. This should land you just past the SW corner of the Tax Dept. Bldg. on the Harriman Campus opposite the north end of Rugby Road.

|

| Note: “Sandbergh“ is where Swinburne Park is; “Tweede Sandbergh“ is where Bleecker Apartments now are; and “Kuyl“ is where the Campus Pond and Indian Quad at SUNYA now are. |

Four miles or 320 chains from the beginning point at the bend in Gansevoort Street. No! The location of Trader’s Hill is not quite solved yet. The problem here is that our Natural NW line doesn’t quite match the match for where it hits Margriets Bergh. In fact it doesn’t hit it. Instead it hits the south end of a remnant of a very large parabolic sand dune about where the Albany Hospital’s extremely ideal fresh air TB Sanatorium used to be, near the west end of the Harriman Campus, by it’s inner perimeter road. Health giving aromatic aerosols are said to emit from evergreen trees. This spot lines up right with the drawing of the parchment map, but it is west of the four mile mark instead of east of it. By the parchment map’s own scale Margriets Bergh is found to be 14 chains or 924 feet east from the four mile mark. Now measure this back along the NW line on the topo map. It comes out even with Eagle Hill, a high eminence set between Western Avenue and the outer perimeter road of the Harriman Campus. But it remains that the line runs a little north of Eagle HIll instead of through it. These are the two high hills that could qualify, but which one is Trader’s Hill? One is too far west, the other too far south. Well! I would give up, at this point, and consider it a toss of the hat, save for one additional as yet, unused puzzle piece.

What’s In A Name?

Sometimes a lot can be in a name. Take “Ye Noonda It Shut-Chera” the Mohawk name for Margriets Bergh in the 1836 article quoted in Part I of this essay. Another version of the same name: “Yonondis-Itsutchera” is quoted likewise in Part I from Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s Aboriginal Places Names of the State of New York, 1845. In this book Schoolcraft translates the Mohawk name as “Hill of Oil.” As to why, no one still knows. Later on in 1906, the eminent priest and ethnologist, Rev. William M. Beauchamp wrote his own Aboriginal Place Names of New York. This was published by the State Education Dept. as “Museum Bulletin 108 Archeology 12.” In this work The Rev. Beauchamp frequently comments on Schoolcraft’s observations. On page 18 of this work under “Albany County“ is to be found the following: “The Indian title was so soon extinguished in most of Albany County that few local names remain. It belonged to the Mahicans, but for their safety they lived mostly on the east side of the Hudson and the Mohawks had names only for prominent places. Those given by Schoolcraft alone may be of his own invention.” Schoolcraft was known for doing this at times, and very cleverly and convincingly so. It’s doubtful however, that this was the case with “Yonondis-Itsutchera” since it appeared first in 1836. The spellings were different in the 1836 source, and Schoolcraft seemed not to have read it, as he didn’t report the Dutch name for the hill. By the way, there are at least two prominent places in the Pine Bush with Mohawk names. On page 20 of the above cited work Beauchamp continues, “It-sut-chera is a name of his assigned to Trader’s Hill, once three miles northwest of Albany. He prefixed Yonnondio, Great Mountain, and then defined it: ‘Hill of Oil.’ This is not satisfactory, nor do I find any such word relating to oil in Iroquois dialects.”

A Missing Piece Completes the Puzzle

In the summer of 1894, an American historian in Amsterdam made an extraordinary and startling discovery in someone’s attic there. The historian was James Grant Wilson, author of Memorial History Of The City Of New York. The lost manuscript found collecting dust in an Amsterdam garret for 259 years was a journal kept by Harmen Meyndertse van den Bogaert. He wrote the journal as leader of a diplomatic delegation sent from Fort Orange to the Mohawks in 1634. At the end of the van den Bogaert Journal is a vocabulary of Mohawk words with their Dutch equivalents. Grant’s translation of this document, published in 1896 as the Report of the American Historical Association for 1895, reveals the following in it’s Maquas (Mohawk) vocabulary: “Maquas: Schakcari English: Eagles.” (The original manuscript resides in the Henry E. Huntington Library in San Marino, California.) This matches well with the 1836 “It-Shut-Chera“ and Schoolcraft’s “Itsutchera“ reported in 1845. It might be helpful to consider the “It” to be an article or particle or prefix, or something like. “It“ can be removed, which leaves Shut-Chera, or sutchera, both being basically the same as “Schakcari.” Therefore, I will English “Ye-Noonda-It-Shut-Chera” as “Hill of the Eagles”and identify it with the hill called Eagle Hill at the corner of Western Avenue and Oxford Road in Albany. This hill is where St. Paul’s Lutheran Church of Albany has maintained their cemetery since 1859. We owe it to St. Paul’s that Eagle Hill has been preserved. Otherwise it surely would have been levelled for more inner suburban streets with English academic names, or for an addition to the Harriman State Office Campus. Eagle Hill or Hill of the Eagles, can now be recognized as a visible landmark of Dutch and Mohawk history in the Pine Bush, in addition to being consecrated space, it’s significance to the Lutheran Church, and to local nineteenth century German American history. Remember William Beauchamp’s sage advice that wherever you live, you can look all about your area, and you’ll always find and learn much of wonder and interest.